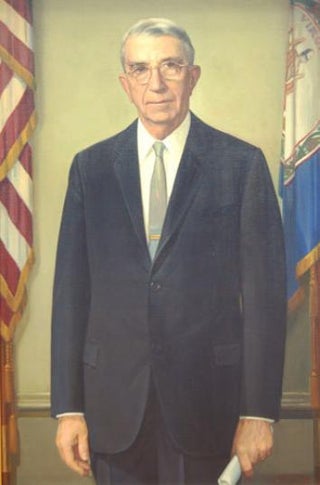

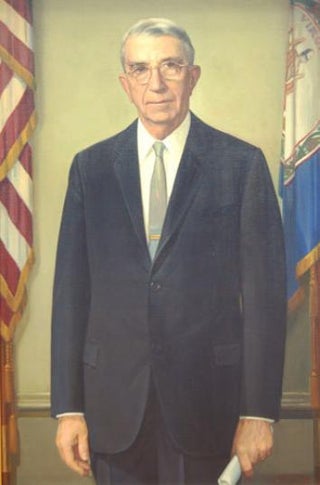

Fifty years ago this week, on Feb. 8, 1964, Rep. Howard W. Smith, a segregationist Democrat from Virginia, stood on the floor of the House to propose an amendment to the Civil Rights Act. Title VII of the bill, which the chamber had been debating for a week, was written to ban employment discrimination because of race, color, religion, and national origin. To the list, Smith added one more category: sex. The House, which counted just a handful of female members, erupted in laughter. “I am serious,” Smith drawled. “It is indisputable fact that all throughout industry women are discriminated against.” In that moment Smith helped catalyze the modern feminist movement—even though, or perhaps because, his motives were hardly feminist. Smith’s mischievous intervention has long been told as an amusing footnote, and opponents of expanded women’s rights, especially early on, used it to stymie efforts to expand gender equality in the workplace. But the story deserves more attention, because beneath its surface lie the sort of ironic complexities that often define our political history. The tale of Smith’s amendment is really about the circuitous and unpredictable ways that legislators and activists combine to push society forward.

Smith had previously tried all sorts of tricks to block Title VII from becoming law as the chairman of the Rules Committee, which approves legislation before it gets to the House floor. Adding sex to the bill, he figured, could undermine Title VII by forcing the government to spend time and resources cracking down on discrimination based on gender, and not just race. At the very least, he hoped to cause mayhem among the liberal supporters of the bill, many of whom had an easier time imagining racial equality than gender equality.

AdvertisementStill, the amendment passed, and when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, it became illegal for employers to discriminate on the basis of sex. It was a moment when women’s rights activists were finally making other gains—most notably with the 1963 Equal Pay Act, which mandated the same wages for the same work and which John Kennedy signed. When Title VII of the proposed act was added a few months later, the activists saw a chance for an even bigger gain. Adding one word—“sex”—to the list of protected classes could revolutionize the workplace. The problem was, no one wanted to introduce the amendment: Even the groups’ allies were afraid it would scare off tentative conservative supporters of the Civil Rights Act, who might support a bill to help minorities, but not women. So the women turned to Smith.